Read time: 7 minutes

This issue is a bit longer than usual, but I think it’s worth it.

Today I’ll show you how I’ve been using Clean Architecture to structure my ASP.NET Core applications.

The principles and patterns of Clean Architecture will help you build systems that are easy to maintain and evolve over time.

Unfortunately, many folks get lost when trying to apply the Clean Architecture principles in the real world.

But today you’ll learn how to map the theory to a practical implementation so you can start building systems that are:

- Testable

- Independent of frameworks

- Independent of the UI

- Independent of databases

- Independent of external services

Let’s dive in.

What is Clean Architecture?

Clean architecture is an architecture pattern that emphasizes:

- The separation of concerns

- The independence of different components within a system

It was created by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob) and it’s based on the SOLID principles, that he also coined.

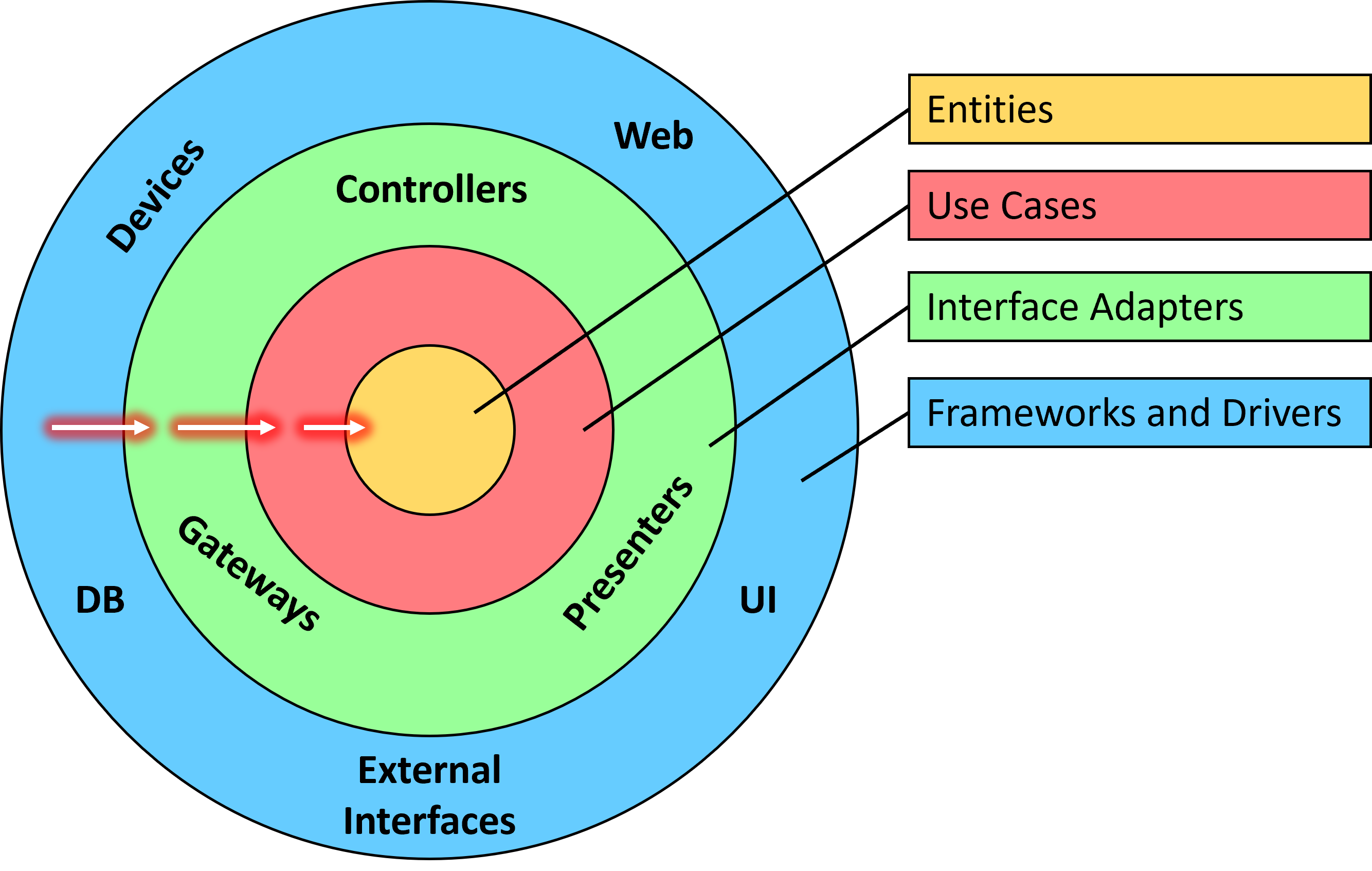

Which are the Clean Architecture circles?

There are 4 circles in Clean Architecture:

Let’s describe each one of them briefly:

Entities

- Represent the enterprise-wide business rules

- Can be used across many apps

- Are the least likely to change when something external changes

- Examples: User, GameMatch, Order

Use Cases

- Represent application specific business rules

- They orchestrate the flow of data to and from the entities

- External changes won’t affect this layer

- Examples: Create User, Match Players, Place Order

Interface Adapters

- They convert data from use case format to external format (and vice-versa)

- No code inward of this circle knows about external details

- Examples: Repository, Controller, Endpoint, Background Service

Frameworks and Drivers

- The place where external frameworks and tools live

- Everything here are details that won’t impact inner circles

- Examples: ASP.NET Core, Angular, React, SQL Server, Cosmos DB, Azure, AWS, Stripe

The Dependency Rule

This is the key rule in Clean Architecture:

Source code dependencies can only point inwards and nothing in an inner circle knows about anything in an outer circle.

So, for instance, use cases can only take dependencies on entities, but never on controllers, endpoints or concrete repository implementations.

A Practical ASP.NET Core Implementation

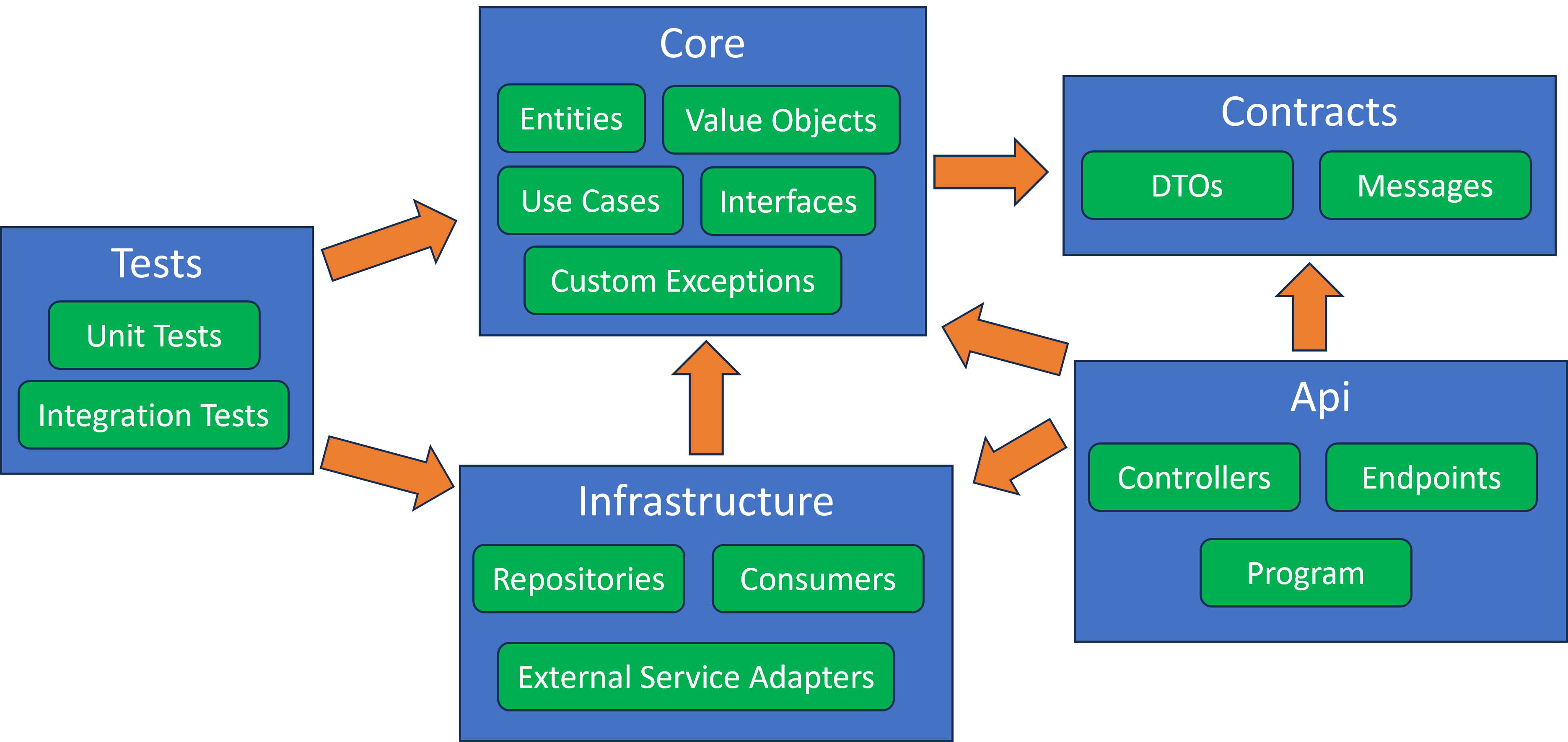

Now, how do those circles translate into the structure of an actual ASP.NET Core application?

Here’s where guidance varies since Uncle Bob said nothing about how to do this on any specific tech stack.

There already dozens of reference implementations out there, with some of the most popular ones being the templates created by Jason Taylor and Steve Smith.

But here I’ll show you how I’ve been doing it:

Core

Instead of standing up different projects for the Entities and Use Cases circles, I prefer to keep them together in a single project called Core.

Yes, theoretically you should have Entities apart, so you can reuse them across multiple systems in your organization (perhaps as a NuGet package?).

But in practice, I’ve never seen a system that requires this. Especially when you do microservices, where each microservice will fully own their domain, so there’s no need to share entities across systems.

Here’s the GameMatch entity (shortened for brevity):

public class GameMatch

{

public GameMatch(Guid id, string player1)

{

// Validate parameters here

Id = id;

Player1 = player1;

State = GameMatchState.WaitingForOpponent;

}

public Guid Id { get; }

public string Player1 { get; }

public string? Player2 { get; private set; }

public GameMatchState State { get; private set; }

// More properties here

public void SetPlayer2(string player2)

{

ArgumentException.ThrowIfNullOrEmpty(player2);

Player2 = player2;

State = GameMatchState.MatchWaitingForGame;

}

}

Regarding the Use Cases, I call them Handlers here, with each one being a small class dedicated to handle one, and only one use case.

Here’s MatchPlayerHandler (logging removed for brevity):

public class MatchPlayerHandler

{

private readonly IGameMatchRepository repository;

private readonly IBus bus;

private readonly ILogger<MatchPlayerHandler> logger;

public MatchPlayerHandler(IGameMatchRepository repository, IBus bus, ILogger<MatchPlayerHandler> logger)

{

this.repository = repository;

this.bus = bus;

this.logger = logger;

}

public async Task<GameMatchResponse> HandleAsync(JoinMatchRequest matchRequest)

{

string playerId = matchRequest.PlayerId;

GameMatch? match = await repository.FindMatchForPlayerAsync(playerId);

if (match is null)

{

match = await repository.FindOpenMatchAsync();

if (match is null)

{

match = new GameMatch(Guid.NewGuid(), playerId);

await repository.CreateMatchAsync(match);

}

else

{

match.SetPlayer2(playerId);

await repository.UpdateMatchAsync(match);

await bus.Publish(new MatchWaitingForGame(match.Id));

}

}

return match.ToGameMatchResponse();

}

}

There will also be a Repositories folder here, which only contains the repository interfaces, but not the concrete implementations, which belong in the Infrastructure project.

Here’s IGameMatchRepository:

public interface IGameMatchRepository

{

Task CreateMatchAsync(GameMatch match);

Task<GameMatch?> FindMatchForPlayerAsync(string playerId);

Task<GameMatch?> FindOpenMatchAsync();

Task UpdateMatchAsync(GameMatch match);

}

Similar to Repositories, sometimes I also have a Services folder here, with a bunch of interfaces to interact with other infrastructure services.

Lastly, there’s an Extensions class to provide a single method to register all the Core dependencies:

public static IServiceCollection AddCore(

this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddSingleton<GetMatchForPlayerHandler>()

.AddSingleton<MatchPlayerHandler>();

return services;

}

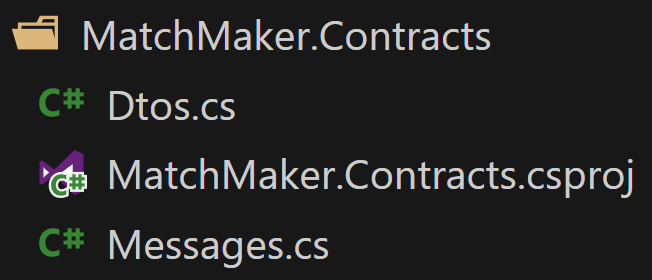

Contracts

This one is not mentioned anywhere in the Clean Architecture theory, but I find it necessary.

This is where all DTOs and messages used to interact with clients or with other microservices live.

Since other teams will usually want me to provide a NuGet package with all those contracts, it’s ideal to keep them in their own project, where they can be turned into a NuGet package easily.

These contracts are used as inputs and outputs for the use cases, so the Core project must have a dependency on the Contracts project.

Is that super clean? Can’t tell, but it’s the best I could come up with.

Here are the DTOs used by the MatchPlayerHandler:

public record GameMatchResponse(Guid Id, string Player1, string? Player2, string State, string? IpAddress, int? Port);

public record JoinMatchRequest(string PlayerId);

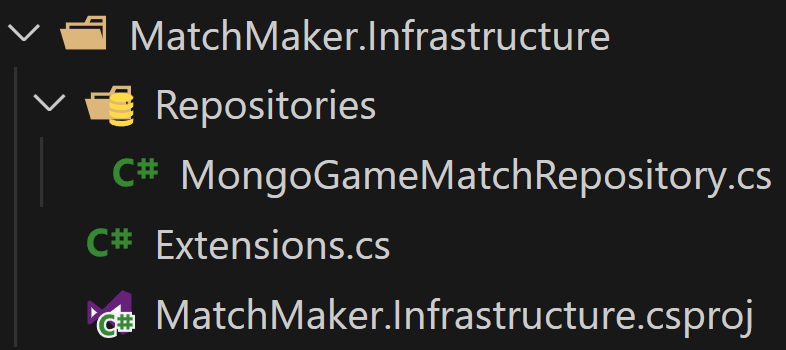

Infrastructure

This is where the Interface Adapters live, and therefore this project is allowed to get a dependency on pretty much any external framework.

In my example it looks small, but it’s usually pretty big since here’s where you’ll find the concrete implementations of any interfaces defined in the Core project and that are needed by the handlers that drive the use cases.

Notice how this is the only project that knows that we are using Mongo DB. The Core project has no idea about that.

And, before you ask:

Yes, if you are using Entity Framework, here is where you implement a concrete EF repository. Your Core project should have no idea that you are using Entity Framework.

Here’s MongoGameMatchRepository (most method implementations removed for brevity):

public class MongoGameMatchRepository : IGameMatchRepository

{

private const string collectionName = "matches";

private readonly IMongoCollection<GameMatch> dbCollection;

private readonly FilterDefinitionBuilder<GameMatch> filterBuilder = Builders<GameMatch>.Filter;

public MongoGameMatchRepository(IMongoDatabase mongoDatabase)

{

dbCollection = mongoDatabase.GetCollection<GameMatch>(collectionName);

}

public async Task<GameMatch?> FindMatchForPlayerAsync(string playerId)

{

var filter = filterBuilder.Or(

filterBuilder.Eq(match => match.Player1, playerId),

filterBuilder.Eq(match => match.Player2, playerId));

return await dbCollection.Find(filter).FirstOrDefaultAsync();

}

public async Task<GameMatch?> FindOpenMatchAsync()

{

// Find an open match

}

public async Task CreateMatchAsync(GameMatch match)

{

// Create the match

}

public async Task UpdateMatchAsync(GameMatch match)

{

// Update the match

}

}

I also have a Extensions class there to provide a single method to register all the infrastructure dependencies:

public static IServiceCollection AddInfrastructure(

this IServiceCollection services,

IConfiguration configuration)

{

services.AddSingleton(serviceProvider =>

{

MongoClient mongoClient = new(configuration["DatabaseConnectionString"]);

return mongoClient.GetDatabase(configuration["DatabaseName"]);

})

.AddSingleton<IGameMatchRepository, MongoGameMatchRepository>();

services.AddMassTransit(configurator =>

{

configurator.UsingRabbitMq();

});

return services;

}

Notice that AddInfrastructure eventually makes this call:

services.AddSingleton<IGameMatchRepository, MongoGameMatchRepository>();

And that’s where the dependency inversion magic happens.

So, when MatchPlayerHandler is instantiated, it will receive an instance of MongoGameMatchRepository, but it will have no idea that it’s a Mongo repository since it only knows about IGameMatchRepository.

Cool stuff!

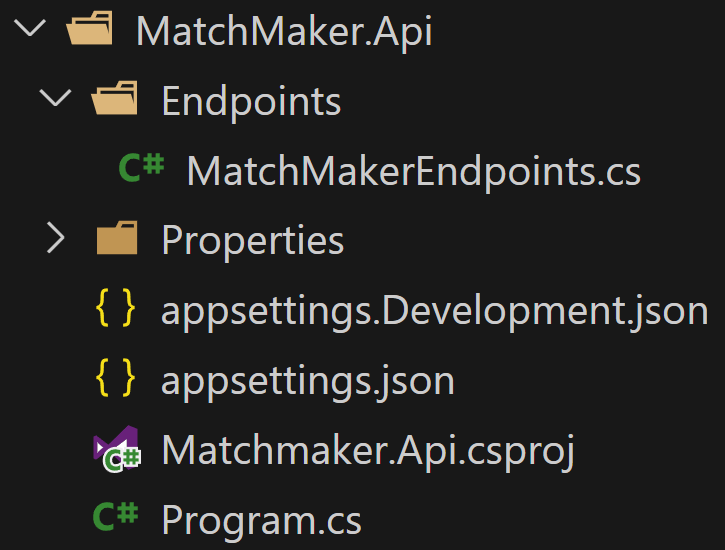

API

Here’s where you’ll define all your controllers and endpoints.

Here are the endpoints:

public static class MatchMakerEndpoints

{

public static RouteGroupBuilder MapMatchMakerEndpoints(this IEndpointRouteBuilder routes)

{

var group = routes.MapGroup("/matches");

group.MapPost("/", async (JoinMatchRequest request, MatchPlayerHandler handler) =>

{

return await handler.HandleAsync(request);

});

group.MapGet("/", async (string playerId, GetMatchForPlayerHandler handler) =>

{

return await handler.HandleAsync(playerId);

});

return group;

}

}

And, during startup, in Program.cs, you’ll have something like this:

builder.Services.AddInfrastructure(builder.Configuration)

.AddCore();

Which takes care of registering all the dependencies in the Core and Infrastructure projects.

Tests

Lastly, we got our test project, which is where all the automated tests live.

And here’s where one of the key benefits of Clean Architecture comes into play:

You can focus your unit tests on the business rules (entities and use cases) without having to worry about any external dependencies.

This is possible because the Core project has no dependencies on any external framework, so you can easily mock any collaborators via the repository and service interfaces defined in Core.

Here’s one of the MatchPlayerHandler unit tests:

[Fact]

public async Task HandleAsync_ExistingOpenMatch_ReturnsMatch()

{

// Arrange

GameMatch match = new(Guid.NewGuid(), "P1");

repositoryStub.Setup(repo => repo.FindMatchForPlayerAsync(It.IsAny<string>()))

.ReturnsAsync((GameMatch?)null);

repositoryStub.Setup(repo => repo.FindOpenMatchAsync())

.ReturnsAsync(match);

GameMatchResponse expected = new(match.Id, match.Player1, "P2", GameMatchState.MatchWaitingForGame.ToString(), null, null);

var handler = new MatchPlayerHandler(repositoryStub.Object, busStub.Object, loggerStub.Object);

// Act

var actual = await handler.HandleAsync(new JoinMatchRequest(expected.Player2!));

// Assert

actual.Should().Be(expected);

}

And when you are done adding tests for Core, you know that you have a solid foundation that you can build on top of.

So, what do you get by using Clean Architecture?

In concrete terms, here are the benefits I’ve gotten in my projects by using Clean Architecture:

- I can easily make changes to my core business rules (entities and use cases) since they are centralized in one place, and they are not mixed with any infrastructure concerns.

- I can easily unit test those business rules without having to worry about any external dependencies.

- It’s easy to understand my use cases since they are small classes that only have one responsibility.

- I don’t have to worry about the database I ultimately choose to use. I can start with an in-memory repository and then switch to Mongo DB, Entity Framework with SQL Server, Cosmos DB, etc. without having to change any code in the Core project.

- In fact, I can switch any infrastructure piece without having to change any code in the Core project, which protects me from unnecessary regressions.

- My endpoints or controllers are super lean since all they do is invoke a handler and return the result. Because of this I don’t worry much about unit testing them (let integration tests take care).

But I think the most important benefit is this:

It encourages me to not mix business rules with infrastructure concerns, which results in a system that is easier to maintain and evolve over time.

And that’s it for today.

I hope you enjoyed it.

Whenever you’re ready, there are 3 ways I can help you:

-

Building Microservices With .NET: The only .NET backend development training program that you need to become a Senior C# Backend Developer.

-

ASP.NET Core Full Stack Bundle: A carefully crafted package to kickstart your career as an ASP.NET Core Full Stack Developer, step by step.

-

Promote yourself to 15,000+ subscribers by sponsoring this newsletter.